LOOKING AT ANIMALS

CAPC - CÍRCULO DE ARTES PLÁSTICAS DE COIMBRA | COIMBRA | SEP. - DEC. 2020

VACA I | Oil on paper | 120 x 155 cm | 2019

HÍBRIDO | Oil on paper | 155 × 120 cm | 2019

MÚSICOS DE BREMEN | Oil on paper | 155 × 120 cm | 2019

OXI I | Oil on paper | 155 × 120 cm | 2019

GALINHA | Oil on paper | 155 × 120 cm | 2019

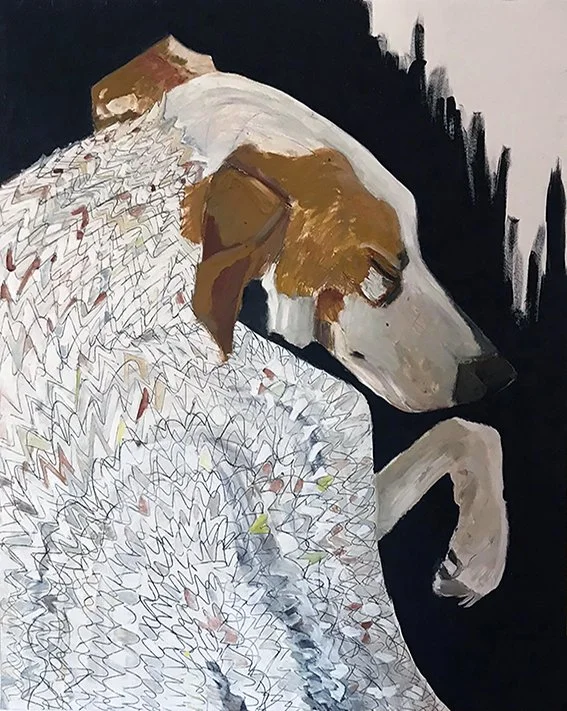

OXI II | Graphite and oil on paper | 155 × 120 cm | 2019

VACA II | Oil on paper | 155 × 120 cm | 2019

Exhibition views

THE LOOK AS A GESTURE, AS A BODY

In the work of Joana Villaverde, the relationship with the Other is built

on a line of relationships that invariably confronts us with the body, with a certain context where that body expands or, on the contrary, contracts itself, rediscovering its meaning in other morphologies that apparently avoid the human figure, but draw from it a sense of life that inspires us to rethink ourselves as beings in relationship who look and recognise one another, be they animals, in the most literal sense of the term, or humans, in that ethical, moral and political sense that defines us.

Let us consider, for instance, the titles of two of her exhibitions, as well as the context in which they inscribe themselves in her work, confronting us with pieces in which life and art interweave in mutual correspondences, like a fusion of act, gesture and thought that transcends its own limits. The first, Animal Nightmare (2015), is the product of a residency in the Middle East, more specifically in Palestine, where the artist intensely shared the violent and traumatic everyday life of those who reside in that part of the world. The second is the present exhibition, Looking at Animals, which was developed in her studio in Avis, where she lives and works. In both exhibitions, but most essentially in the latter, the works, which include oil paintings, drawings and video pieces, are strongly marked by a vigorous drawing, sometimes close to expressionism, and depict various animals. However, the artist does not resort to fabulation, does not develop an illustrative visual narrative, or even try to depict any of the animal figures in anthropomorphic terms that might transmute them. Doubt, if by any chance it exists, resides in the look these animals direct at us and the way we interpret that look, which projects itself outwards of the field of the drawn (or sometimes painted) image. Here, we are back to the relationship with the Other, with the others, with our look and with the spaces and places they inhabit, which live on in the everyday life of the artist, independently from the various geographies her concerns and interests have explored. Even when her gaze focuses on a particular place, such as her studio, it is still a part of the life that occurs daily before that landscape, those atmospheric and luminous changes that pass through the wide windows creating a time of its own, the time of the construction of each piece, experimenting and working with a variety of scales and formats. To all this is added, and quite importantly, her interest in literature and cinema, which constitute themselves as heterotopies that interweave in a cumulative process that is sometimes contradictory, in the sense that the artist generates a deconstruction of these imagined spaces, fragmenting and dissecting each moment and each fictional place, which gradually reveal themselves as an individual, a name or under a given condition. This notion of what might condition an image, or depicted entity, is present in the titles of the pieces, namely in “HÍBRIDO” [HYBRID]. The piece is like a close-up shot of the head of an animal, which we can hardly identify due to its closeness or similitude to others. It can belong to a dog or a horse, or to some mythical creature, but it may be just one head on a dark, earthy background, looking at us and opening its jaws like it was screaming at us, or perhaps uttering a call we will never hear, but which will remain there, inexorably stuck to the oil paint’s magma that imposes itself in a series of layers, laid down with powerful physicality.

Likewise, the written language, which is present in the titles, sometimes less immediately comprehensible, as is the case of “OXI”, which applies to two large format paintings that depict a dog, or to a small drawing with a line that appears to define a seemingly abstract profile, confronts us with a deception. What is Oxi, or why? Oxi is a Greek word, an adverb of negation. One of the works, “OXI II”, displays a close-up of the animal’s gaze, while “OXI I” confronts us with a body stance that we could almost liken to a contraction or defensive movement. This second piece is apparently unfinished: the black oil paint on the background does not cover the whole surface of the paper and the animal’s body is drawn as if it was covered with scales, or with a vitreous fur, the result of a convulsive and repetitive motion of the hand, which draws quickly but not lightly, placing the animal’s head, painted in oils, on the place where the viewer’s eye focuses. The title of the two works highlights that heterotopic geography, in which the vernacular, everyday side of the artist’s life coexists with a social awareness of her time. Oxi is thus both an adverb of negation and a word that exists in a paradoxical realm, somewhere between affection, chance and the need to displace the meaning of an event. On the one hand, it is closely connected to the name of the depicted animal, the artist’s dog, and on the other to a decisive European political moment, because that word was the most heard slogan during the day of the 2015 Greek plebiscite that rejected the EU’s economical policies for Greece. Joana Villaverde is not acting in celebration of a particular event. Instead, she combines and blends various events that are marked by the collective memory, as well as by her intimate sphere, her home and all who are close to her.

Considering this, and taking into account her already mentioned

interest in literature and film, a book by the philosopher and writer

John Berger, entitled Why Look at Animals?1, will play a crucial role in terms of the reflection that was demanded by the work carried out for the exhibition. The artist confronts us with a sentence that invites us to look attentively at the animals. In principle, this applies to the animals featured in the exhibition, even from a perspective that reminds us of enchanting fables that are also commentaries on human actions, as is the case of “Os músicos de Bremen” [The musicians of Bremen], a composition fragmented across the two axis of the paper that references a German folk tale published by the Brothers Grimm. On the other hand, there are two pieces, entitled “Vaca I” and “Vaca II” [Cow I/II], which perhaps depict animals that inhabit the landscape surrounding the artist, that look like they were taken from screenshots of a film, but nonetheless appear to look at us from the field of the large sheet of paper. The difference lies in that depth of field, between the distance and the proximity of the two animals; in one case, one of them appears to be a reduction, not as a miniature, but as a distant image within the body of another picture of a cow, in a sort of trompe-l’oeil effect that mutes the temptation to create a mere portrayal of those animals.

In one page of “Why Look at Animals?”2, the chapter that gives Berger’s book its title, Joana Villaverde underlined the following passage, which I believe creates a close connection with the title of the exhibition, and thus with us, as viewers: “The eyes of an animal when they consider a man are attentive and wary. The same animal may well look at other species in the same way. He does not reserve a special look for man. But by no other species except man will the animal’s look be recognized as familiar. Other animals are held by the look. Man becomes aware of himself returning the look.”

The artist is playing with a number of depictions that are seemingly banal and somewhat vernacular, but the written word acts here as an index that reconfigures the representation, in much the same way that the gaze, when not reciprocated, inhibits the existence of the one who looks and of the other who is the object of their gaze. That is what we can glean from the small video pieces, from the circularity of the spoken word and the movement of the drawing, in a process of concealment and disclosure that, unlike what happens with the large-scale pieces, causes them to seemingly extinguish themselves into a fragment of time; however, they return, piling themselves up like layered memories. The same can be observed in the smaller drawings, like the two shapes entitled “Golden Egg” and “Egg”.

The pallete of golds, the shape drawn in graphite and the handwritten sentence “uma espécie de ovo” [a sort of egg] are, in the end, nothing more than clues to a self-referential diary that grows out of the particular and into the universal. A diary in which everyday life develops in the sphere of intimacy, but chooses to not hold itself hostage, offering itself to the world through the look that exteriorises itself, while inexorably returning to itself.

JOÃO SILVÉRIO | 2020